John Luther Adams’s In the Name of the Earth, which premieres on August 11 in New York’s Central Park, may rank among the Pulitzer Prize-winning composer’s most logistically ambitious works to date: It calls for 800 singers, divided into four groups and perched around the Harlem Meer, the lake at the park’s northern tip bordered by bluffs and rocky outcroppings.

The text, says Adams, draws on the names of North American rivers, lakes, mountains and deserts. The singers are a mix of amateurs and professionals, and their parts coalesce in the final bars, suggesting rivers flowing downhill and converging in the ocean.

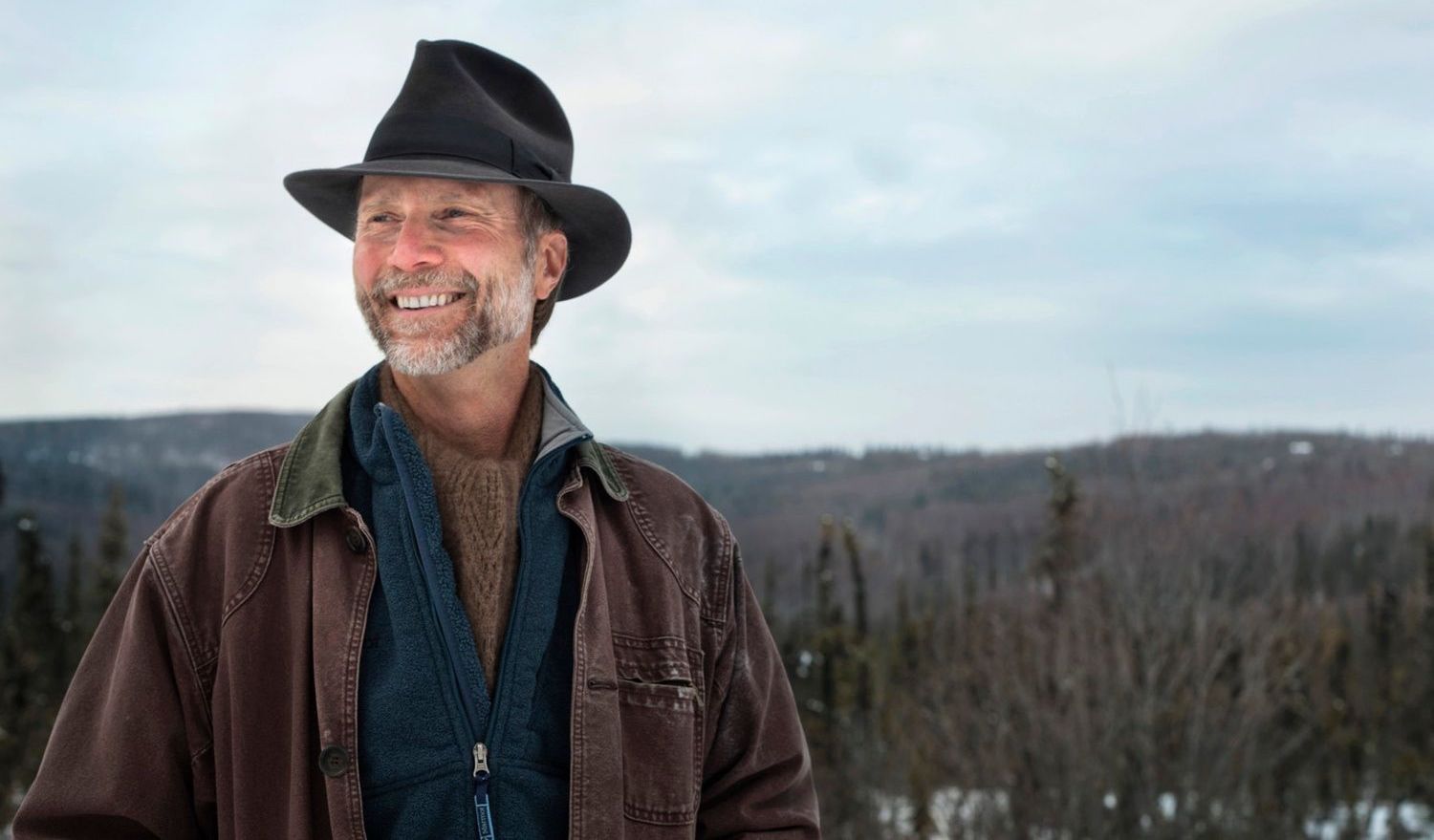

In the August 2018 issue of BBC Music Magazine, Adams tells me about the work’s inspiration − and the challenge of writing political music that doesn’t simply preach to the choir. Here are a few “outtakes” from our conversation, which have been lightly edited for space.

How did you envision the sound of this work given the open, unpredictable setting?

This is not my first rodeo, so to speak. This piece is the latest in a series of outdoor works that began with Inuksuit, the big outdoor piece for up to 99 percussionists. I’ve since done a piece called Sila: The Breath of the World. There’s another piece [Across the Distance] for massed French horns all across the distance.

I’ve learned some things along the way about technically what works and what doesn’t work. I began with Inuksuit [to consider] what might constitute an authentic outdoor music. How is it fundamentally different to make music outdoors than it is indoors? I realized that indoors we are trying to shut ourselves off from the world and concentrate our attention deeply on a relatively few carefully-composed and beautifully-produced sounds that we imagine as the music. Anything else we regard as an interruption.

But outdoors, we’re encouraged to turn that inside out and listen as far as the ear could hear. Maybe we’re hearing things that we don’t see, and we’re not even sure where they’re coming from. It encourages a fundamentally different kind of listening. It’s an extroverted listening.

How was the Harlem Meer chosen as a location?

My wife suggested it. Our apartment in New York is just a few blocks from there. She takes her walk there every day. I run everyday and Central Park through the North Woods and around the reservoir. So we know that part of the park well. I had my eye on some other sites around the city but my beautiful wife Cynthia who is both the good looks and the brains of the outfit came back from her walk, and said, ‘You know, you ought to look over there on those knobs, those outcroppings on the south shore of the Harlem Meer.’ I think that might be a good spot and she was right.

How much time did you spend there sussing it out?

I’ve been over there any number of times making sketches on my own about how we might stage the thing and it was very helpful. I was still composing the piece while we were looking at the site and it is not site-specific. These outdoor pieces are not assiduously tied to a certain location.

To what extent are you taking a stance on the Trump administration’s policies on the environment with this piece?

I’ve been politically active since I was marching the streets when I was 16 and I was an environmental activist professionally for a decade. So I’m no stranger to politics. But my life is rooted elsewhere. My life is dedicated to the art of music.

The music always has to come first. If it doesn’t, then all of the other associations that I might hang on it through interviews or titles or program notes really are just nonsense. It’s so much ‘blah blah blah.’ It’s got to move you, it’s got to touch you, it’s got to succeed as music. Otherwise, what am I doing? I should run for office.

And you could argue that you’re preaching to the converted.

Yeah, I’m a little bit concerned about that. And in this case, it’s especially funny because I don’t want to be literally singing to the choir.

Read more in the Aug. 2018 North American edition of BBC Music Magazine.