For all of the iconic protest music that came out of the 1960s and early ’70s, classical composers mostly stayed at a remove from that decade’s turbulent events. There were a handful of noted exceptions, of course, including Terry Riley, La Monte Young, George Crumb and Karlheinz Stockhausen, but their works were not exactly staples of mainstream orchestral programming. Now, fifty years on, composer Julia Wolfe aims to evoke the decade and its sounds in a new 30-minute orchestral work called Flower Power.

The New York-based Wolfe, who won a Pulitzer Prize for her 2014 oratorio Anthracite Fields, has been increasingly drawn to subjects involving American history and the plight of the working class. A year ago, for example, the New York Philharmonic gave the premiere of Fire in my Mouth, her much-discussed oratorio about the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire.

Flower Power will be premiered by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, along with the Bang on a Can All-Stars (which Wolfe co-founded), at Walt Disney Concert Hall on January 18-19. John Adams will conduct. I recently spoke with Wolfe by phone for the January 2020 issue of BBC Music Magazine. Below are excerpts from our conversation.

Your recent orchestral works, including Anthrocite Fields, and Fire in My Mouth, have been inspired by American history or social themes. What motivated your newest work, Flower Power, which is a meditation on the 1960s?

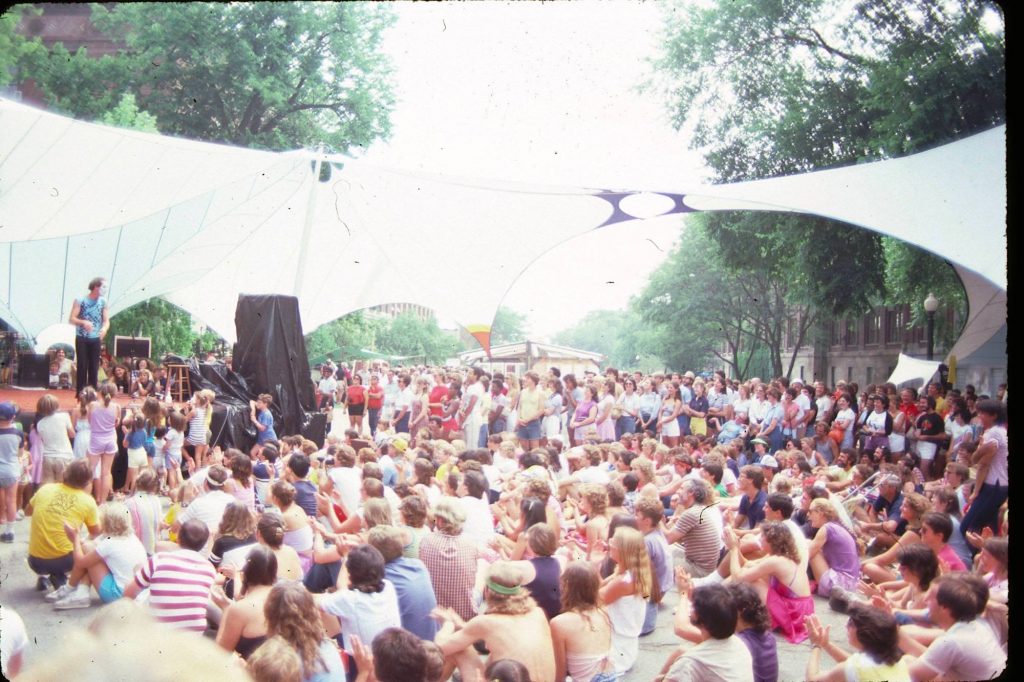

I was doing a lot of reading about the sixties and mostly listening to music of the era. Of course, I was a baby when that time period was going on. I’m not a child of the sixties, but I went to college in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and lived there a few more years. It still held onto the spirit of the sixties for another 25 years or so. And there’s still a very strong sense of activism and concern about the world there.

At the time [the 1960s], there was this optimism among young people and almost this euphoria about being able to make change. I was harkening back to that because we need it [today]. Part of me had this desire to tap into that idealism.

How does this 1960’s spirit play out in the music?

It’s a natural world for our band, the Bang on a Can All-Stars, which has a really broad musicianship and a broad sensibility. They’re really comfortable in the rock, jazz and folk worlds. Mark Stewart, the guitarist in the group, is one of the two original members and he’s also Paul Simon’s music director, so he lives in lots of different worlds. He’s just one example. I have this great, crazy riff in the piece and they all can lock in on this groove together. And we’re trying to bring some of the sensibility and the chirpiness of the time period into the big orchestra sound.

Did you find yourself quoting or evoking the songs of that era?

I can’t point to specific things that I listened to so much. I went back and listened to Led Zeppelin, Joni Mitchell and the Beatles. That kind of psychedelia comes into the music with the choice of instruments and the kind of trance-like sensibility. If I quoted, I didn’t know it. So we’ll find out!

I understand Flower Power also comes with psychedelic visual projections.

That’s right. And I have this collaborator, Jeff Sugg, who has been a part of a lot of shows on Broadway. The first time we worked together was in Anthracite Fields. He did all of the same research that I did for that piece [about Pennsylvania coal miners]. He went to the coal mining region in Pennsylvania and gathered all kinds of documents and maps and photographs. He was probably paralleling what I was doing in response to the music. Then, I also have a low-key director, Annie Kaufman, so she added some really beautiful but subtle movement [to Flower Power].

It seems that orchestras are giving you a lot of leeway to explore different sounds and textures.

Yes, the orchestra makeup is changing all the time. In Fire in My Mouth I added an electric guitar and electric bass. I felt like I needed that metallic sound and there’s more flexibility instrumentation-wise… In the last couple pieces the players were pretty open. I used a lot of crunchy sounds. There are some in this piece too. I use a lot of noise and distorted sounds that are not traditional orchestral sounds; I also use a lot of good distorted guitar sounds. But I think people’s ears have changed. It’s not like it was even a few years ago.

Interview has been condensed and edited for clarity. Read more in the North American section of the Jan. 2020 BBC Music Magazine.

Leave a Reply