Until 150 years ago the West Coast was isolated behind the Rocky Mountains. Then, on May 10, 1869, a game-changer called the Transcontinental Railroad was completed, fully connecting San Francisco, Sacramento and countless small mining towns to the rest of the Union. It made way for the largest movement of orchestras, opera companies and soloists in our history.

In a piece in the May 2019 BBC Music Magazine, I look at the impact of the first Transcontinental Railroad on the concert business:

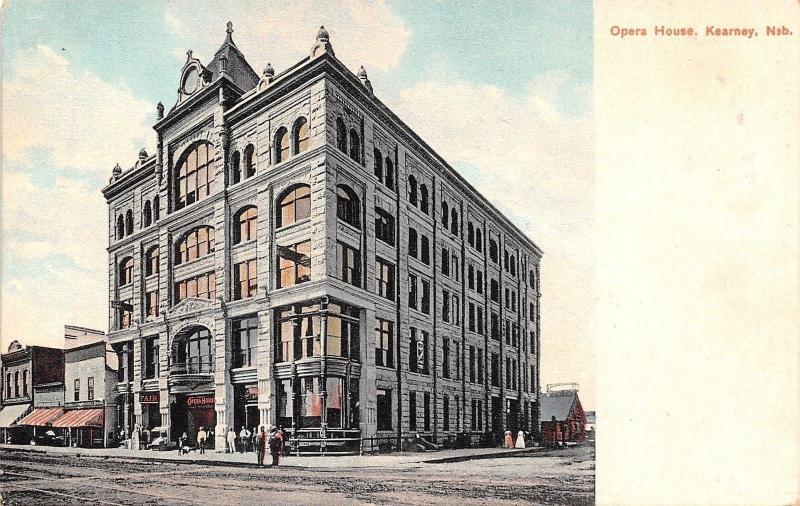

“As the transcontinental railroad opened up the American West, dusty frontier towns with little more than a jail and a saloon aspired to display their growing wealth and ambition. Naturally, this meant culture. Between 1865 and 1900, some 4,000 opera houses were built, from the Corrine Opera House, in Corinne, Utah (1870) to the Downs Opera House in Evanston, Wyoming (1885).

‘As soon as the railroad came to town, or even before its routes were finalized, town fathers, newspaper editors, culture-hungry women, and ordinary citizens campaigned for an opera house on Main Street’, writes Ann Satterthwaite in Local Glories: Opera Houses on Main Street, Where Art and Community Meet.”

Of course, “opera houses” in those days were theaters that presented a variety of musical revues, operettas, magic acts, “horse operas” and minstrel shows, often staged by resident stock theater companies. But the term “opera” signified culture and civilization and, soon enough, East Coast opera troupes and orchestras were crisscrossing the country. These were elaborate productions: the Metropolitan Opera decreed that “everything but the opera house must go” when it traveled the country. For a 1900 tour, 220 company members set off in 16 Pullman cars; musicians amused themselves with rollicking poker games in the dining car.

A postcard for the 1,200-seat Kearney Opera House (1891 -1954), built along the Union Pacific line.

Orchestras also began touring out west, and the New York Philharmonic and Boston Symphony were both hitting the rails by the 1880s. Some of the most eyebrow-raising aspects of these early tours involved the luxurious star quarters, boasting paneled libraries, dining rooms and grand pianos. Again, from the article:

“Divas like Adelina Patti, Nellie Melba and Lilian Nordica traveled in private coaches hooked onto the caboose position (at the end) of a train. Patti had an opulent, $65,000 car with her name in gilt lettering on the side. ‘The diva traveled for years in luxurious seclusion, though hardly in total solitude’, writes Quaintance Eaton in “Opera Caravan: Adventures of the Metropolitan on Tour.” ‘Indeed, she required an entourage of a dozen or so, all of whose fares constituted an obligation of the management — including a personal chef.’ When Patti’s car pulled into Omaha, she opened the blinds to show off her sumptuous quarters.”

Train travel began to wind down in the 1920s, and after World War II, railroads declined as the automobile and plane took off. But the railroad’s legacy hasn’t been entirely forgotten. The Utah Opera this month is presenting four 10-minute operas on themes related to the 150th anniversary. And some 14 American orchestras have co-commissioned Transcend, a piece by Chinese-American composer Zhou Tian marking the occasion. Nevada’s Reno Philharmonic gave the first performances in April, and other orchestras will follow, including the Utah Symphony and the Omaha Symphony.

“It’s a triumph of human spirit and hard work’, Zhao Tian told me, about the railroad. “As significant and magnificent as the structure was, it was at the core a human story.”

Top photo: Paderewski on tour in 1896 (Photo: Paderewski Museum, Morges; George Steckel)

Leave a Reply