Last week, the cellist Sergei Roldugin appeared in the Syrian city of Palmyra, performing a solo while flanked by members of Russia’s Mariinsky Theater Orchestra. The official performance has been described as a victory lap for Russia, whose special forces recently helped recapture the city from ISIS. It also represented a defiant gesture for Roldugin, a former principal cellist at the Mariinsky who last month became a central figure in the Panama Papers leak.

As I explore in a new article for Slate, Roldugin is the latest in a long line of cellists to wade into international politics and other extramusical ventures. Pablo Casals, Mstislav Rostropovich and Janos Starker are the best-known among those who lived under authoritarian regimes and eventually were compelled to flee to the West. There are at least three other cellists whom, for space reasons didn’t make it into my piece, but also merit attention.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j54eOpNCLYA

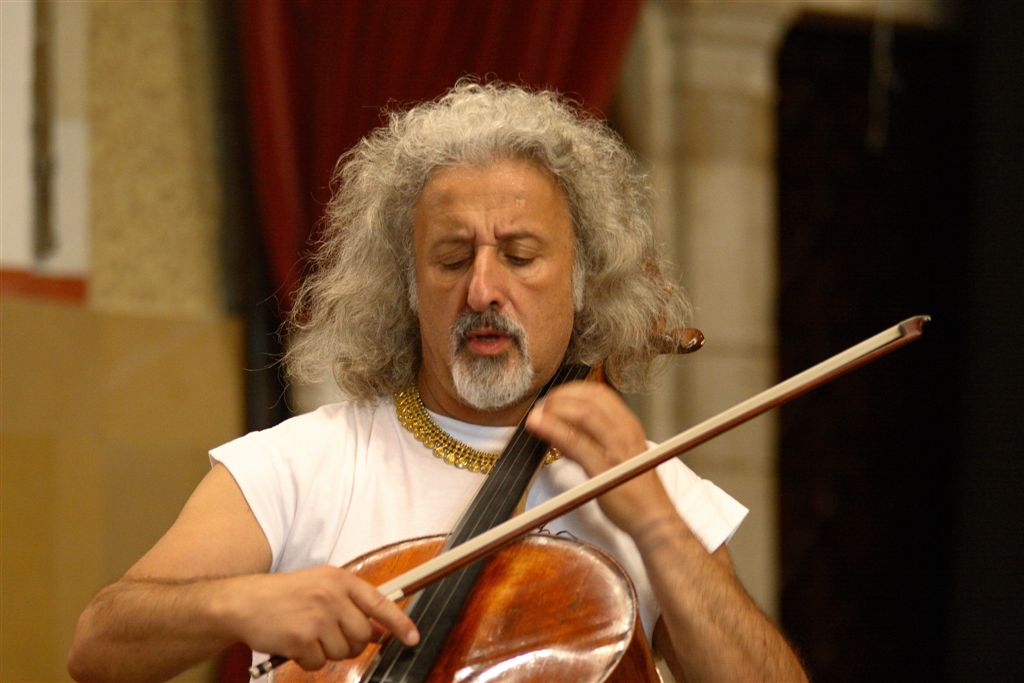

Mischa Maisky

Born in Riga, Latvia in 1948, Mischa Maisky (pictured above) spent 14 months in a Soviet labor camp after having a run-in with the authorities in 1969. His alleged offense: buying a portable tape recorder on the black market in Moscow. He has said it was for recording lessons with his teacher at the Moscow Conservatory; the KGB had other suspicions. “The real reason they arrested me was that my sister and her family had repatriated to Israel in 1969,” he told an interviewer, noting that the authorities assumed he would soon follow her.

After his release from prison, Maisky faked insanity and entered a mental hospital in order to avoid military service. Finally, in 1974, the Soviet authorities allowed him to emigrate to Vienna on the condition that he pay back the entire cost of his education. Today he’s known for his soulful and expressive performances of a wide repertoire.

Pierre Fornier

French cellist Pierre Fournier (1906-1986) overcame childhood polio to build an international career that spanned five decades – and featured more than one brush with totalitarian regimes. In 1949, it was revealed that Fournier had performed 82 times on a German-run radio station during the occupation of France, earning 192,400 francs. The French musicians’ union banned from performing for six months after the revelations surfaced.

Years later, Fournier seemed to atone for his WWII actions by turning down an offer to play in the Soviet Union, citing the Kremlin’s anti-Jewish policies. “I have too many Jewish friends to agree to play in a country with an official policy of anti-Jewish discrimination,” he said in a 1971 interview with the New York Times.

Gregor Piatigorsky

Some of the most colorful tales of escape from the Soviet system can be found in the autobiography of cellist Gregor Piatigorsky (1903-1976). After a turbulent childhood in Russia he fled to Poland in 1921, an escape that involved a river crossing and border guards shooting from all directions. Piatigorsky was well known as a raconteur, and some details of his accounts may have been exaggerated; nonetheless, he led an eventful life, performing in seedy European cafes and brothels before landing a post in the Berlin Philharmonic and eventually, moving to the U.S.

The cellist is now honored with the Piatigorsky International Cello Festival, which this year takes place May 13-22 in Los Angeles.

Why so many rebels with cellos? The paucity of standard concertos (four or five, compared with dozens for the violin and piano) may be one factor in explaining their entrepreneurial tendencies. I asked Ralph Kirshbaum, the Piatigorsky Festival’s artistic director, and he insisted that despite the many renegades, cellists are very collegial artists. “Cellists are very warm and communicative people,” he said. “I know most of the cellists who are playing today and that’s the kind of personality they are.”

Leave a Reply