Most major concert venues offer walking tours that amble through dressing rooms, studios, technical areas, lobbies and nosebleed seats while delivering bits of (official) history and lore along the way. In the April issue of BBC Music Magazine I report on my experiences with five of these in New York and London, as I anonymously signed up with groups touring Lincoln Center, Carnegie Hall, the Metropolitan Opera, Royal Albert Hall, and the Barbican Centre.

I was eager to find out how such tours serve as introductions to their halls. Which ones are the most informative? Which go most “behind the scenes,” and which selectively “edit” their histories?

To some extent, tours sink or swim based on the ability of the guide to both present a lot of information in a digestible format, but also spin a good yarn. The guide at London’s Royal Albert Hall, an whimsical gentleman with a Willy Wonka-like air, delivered well-practiced stories about the arena’s namesake, Prince Albert, who is memorialized with a lobby portrait and 15,000 letter A’s adorning the staircase railings and other nooks. As he whisked us up and down five floors, the guide had a surefire grasp of big numbers: The hall’s dome weighs 600 tons, 400 of which are iron and 200 of which are glass (now covered up). Eric Clapton recently gave his 214th performance at the hall. Cirque du Soleil brings up to 60 truckloads of equipment for performances. The pipe organ is one pipe short of 10,000 pipes.

On the Metropolitan Opera’s backstage tour, numbers were similarly recited by an amiable guide (I was unaware that there are 17 unions there representing the 1,600 employees) but much of the experience was about seeing the inner workings of the company, from the cinder block hallways to studios and workshops. Outside the costume shop, a large, velvety robe was passed around the group as we eyeballed costumes stuffed onto racks and boxes containing prop gun holsters, belts, and military insignia. Opera lore got its due with tales of the great soprano Maria Callas and her tempestuous relationship with former general manager Rudolf Bing.

The Barbican Centre’s brutalist architecture tour was less about performance history than the labyrinthine “city within a city” that rose from the rubble of World War II. Our guide suggested that the Barbican is “a bit like London in a way.” At first, it feels slightly impersonal and cool but once you get to know it, you discover its warmth and personality. She readily admitted to its dysfunctional elements (a main entrance beside a loading dock and a generally walled-off character) but also pointed to the meticulously executed details throughout (including semi-circular forms, wooden shutters and gondola shapes meant to evoke a Mediterranean getaway). One came away with a greater appreciation for a misunderstood chapter in architectural history.

Carnegie Hall has long been skilled at telling its own story, so it was no surprise that the venue’s tour was efficient and compelling. Unlike the Met, it was a front-of-house experience, and it did not venture into Weill Recital Hall or Zankel Hall. But the key milestones were all presented, starting with the choice of location, in what was then a desolate area where real estate was cheap (and is now billionaire’s row). As for the acoustics, “It comes down to one little word. The word is curves,” stated our guide, an endearingly irascible New Yorker. “There are no angles in the house whatsoever. The walls are extremely smooth. There’s no decoration whatsoever. Music has no where to go but in this direction [gesturing upward]. The music keeps going around and around, so no matter where you’re sitting, you’re going to get a perfect sound.”

Lincoln Center’s 75-minute tour had the most ground to cover with its various constituent organizations and venues stretching over 16 acres. The major stories were all there – from the outdated “slum clearance” philosophy that begat the campus in the 1950s and ’60s to the repeated attempts to fix the acoustics in what is now David Geffen Hall. The New York State Theater emerged as the best preserved of the buildings, and we learned how architect Philip Johnson decided to use travertine marble after marveling at its luster at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. “He felt if it was good enough for God, it was good enough for us, so he made sure all of the buildings had it.”

Also sprinkled throughout the tour were little details such as the stuffed birds that adorn a corner of the Geffen Hall lobby, named “Lenny and Max” after Leonard Bernstein and lead architect Max Abramovitz. And in a nod to theater superstition, a stage light always stays on inside Alice Tully Hall, in an effort to chase away mischievous ghosts who populate the theater.

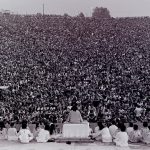

Read here about a previous tour I took of Amsterdam’s Concertegbouw and below, enjoy this time capsule from a rather different era:

Leave a Reply