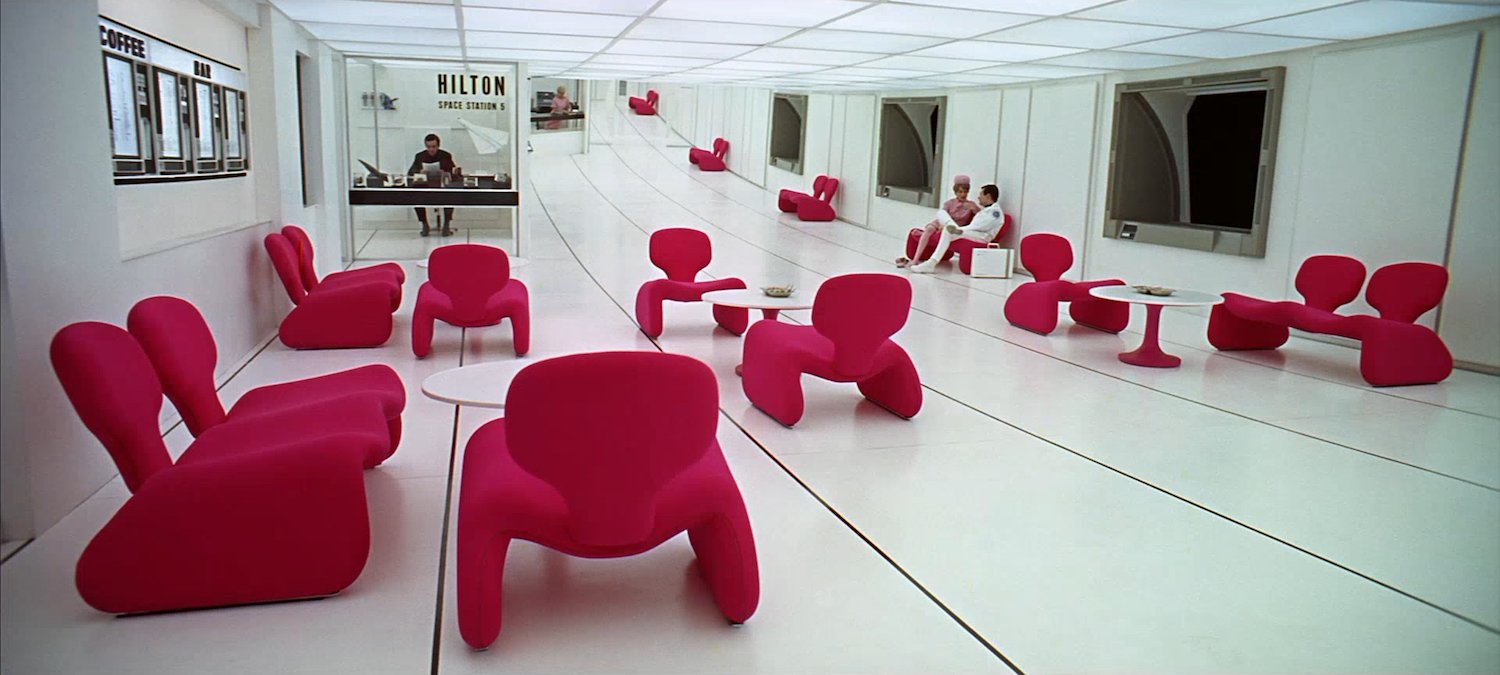

The ongoing craze among orchestras to present films with live soundtracks has split into separate creative strands. One is focused on recent blockbusters where music is of a more secondary appeal: that’s arguably the case with the “Home Alone” franchise or the later “Harry Potter” films. On the flip side are films that place music at the forefront, including “On the Waterfront” (music by Leonard Bernstein), “The Red Violin” (John Corigliano), and most significantly, “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

In the March 2018 issue of BBC Music Magazine, I look at how director Stanley Kubrick threw out sci-fi music conventions in “2001” by using works by Richard Strauss, Johann Strauss, Jr., Khachaturian and Ligeti. At the time of the film’s premiere – 50 years ago this April – sci-fi soundtracks were frequently of a “bloop-bleep” variety, using synthesizers to envision technological music of the future. Strauss Jr.’s Blue Danube Waltz was thus an ironic gesture, linking that future to 19th-century Vienna and highlighting the swirling grace and elegance of the universe.

Kubrick also brought György Ligeti mainstream attention by using the Hungarian modernist’s music to underscore the film’s journeys into the unknown and bizarre. We first hear Atmospheres against a black screen in the film’s opening. The Requiem becomes a signature motif of the mysterious monolith (appearing with Ligeti’s Lux Aeterna), and Atmosphères accompanies astronaut David Bowman’s journey into the psychedelic star gate.

One music-geek side-note about the Requiem. Conductor Brad Lubman notes that because Ligeti’s music was very new – and uncharted territory for singers in 1968 – the performances on the soundtrack made the score seem more modern than the composer had intended.

“There are things that are a little bit microtonal-sounding but it’s not actually written that way,” Lubman said. “There are no microtones. The couple times I’ve done it, what I always said to the choir, ‘Listen, the important thing here is the intention of the music and not so much whether we hear a perfect seven against five,’ or ‘your A-flat was a little too close to your A-natural.’ Because part of what makes that original recording so effective, so disturbing, is this was brand-new music and the height of difficulty.”

Lubman added that after he conducted a live-with-orchestra performance of “2001” at the Hollywood Bowl, he was struck by how Kubrick incorporates silence. “There are long silences where the orchestra’s sitting there and all you hear is the astronaut breathing,” he said. “Or towards the end where [Bowman] is an old man and lying on his bed, you think, ‘Wow man, that’s 20 or 30 minutes [without dialogue or music].’”

After the BBC Music article had gone to print, I received an e-mail from the conductor John Mauceri, who has recorded the music from “2001.” “In short,” Mauceri summarized, “Kubrick and his music editor played with irony (Blue Danube) and gravity-free descriptive (Ligeti) – and of course straight-ahead musical lexicon for immense power as well as empathy for loneliness in traditional classical music terms (Strauss and Khachaturian).”

Indeed, Khachaturian’s unheralded Gayane suite serves an important purpose in “2001”: to create a feeling of eerie isolation as Bowman and Poole are going about mundane tasks aboard the Discovery, while the Hal-9000 does its malevolent work. As with Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra, the music stands on its own, uninterrupted by dialogue or other sound effects.

Leave a Reply