Jay Friedman knew early on what kind of sound Georg Solti was after when the Hungarian maestro became the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s music director in the fall of 1969. “When he first came — and this is regarding the brass section — you couldn’t play loud enough for him,” the orchestra’s principal trombone recalls. “It didn’t matter what it was. Even Schubert’s Ninth Symphony could not be played loud enough. He’d always say, ‘Give me more! Give me more!’”

Friedman and his brass colleagues raised the decibel level and audiences reveled in spectacular sound feasts by Mahler, Bruckner, Tchaikovsky and Wagner. Reviews from the early 1970s describe an almost delirious audience response to such pieces, including one Carnegie Hall ovation that stretched for 20 minutes. After the orchestra returned in October 1971 from its first European tour, it was honored with a parade down State Street in Chicago, with the musicians riding on a trailer truck flanked by motorcycle escorts.

Perhaps more than predecessors Jean Martinon and Fritz Reiner — both covered in the first part of this series — Solti tapped the brass section’s brilliance and visceral power. With few personnel changes during the first 15 years of Solti’s tenure, the players locked into corporate sensibility. Only in the conductor’s later years did that aesthetic begin to shift.

Professional Efficiency

Musicians were at first leery when, in 1968, Solti told the Chicago Tribune that he planned no immediate personnel changes, but “something will certainly have to be done,” given that more than 20 players were approaching retirement age. Some musicians took that as a warning that jobs might be eliminated — and behaved accordingly.

“The players were always prepared and arrived at rehearsal having studied and practiced their parts well,” Solti wrote in his 1997 Memoirs, “and consequently I had to work at the same level, or, indeed, beyond it.” He singled out the work of principal trumpet Adolph “Bud” Herseth (“perhaps the most revered and respected brass player in the entire world”), principal French horn Dale Clevenger (“a brilliant young musician”), and principal tuba Arnold Jacobs (“a sort of father to all tuba players”).

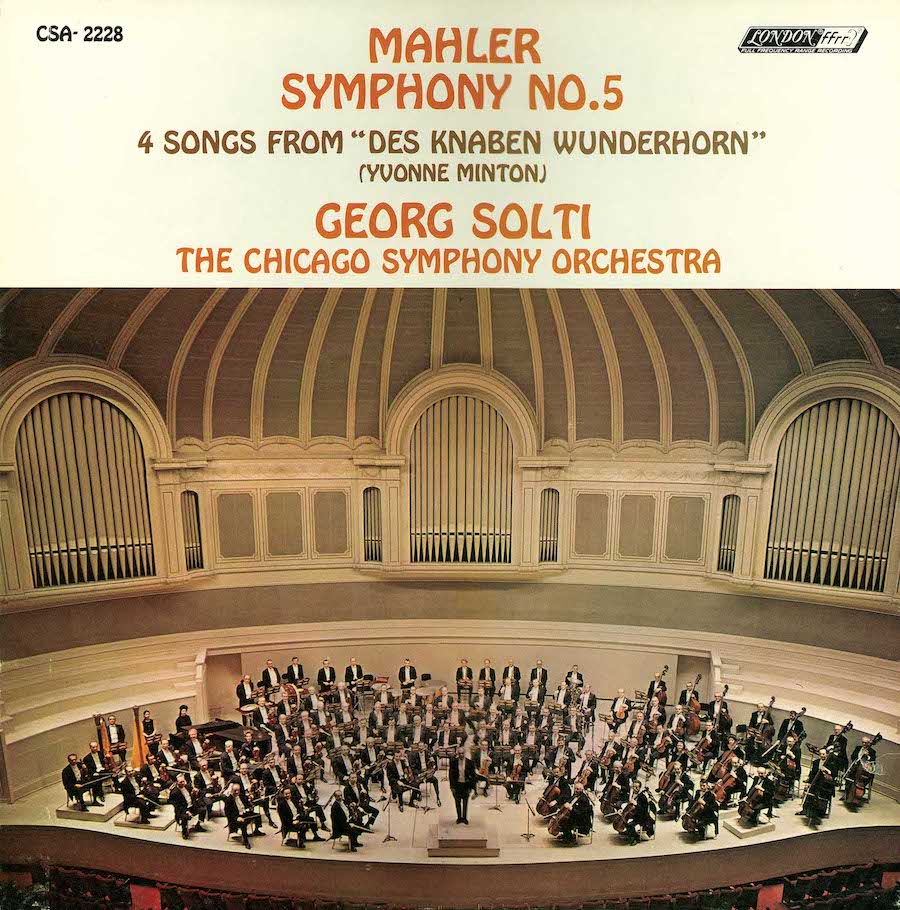

Solti and the CSO got down to business in 1970, recording Mahler’s Fifth and Sixth symphonies, and a selection of the composer’s songs, as part of a new contract with London Records. “With those early Mahler records, you heard this gutsy, confident, emotional playing and you had this supersaturated [recording] capture that brought it right to your face,” says CSO Trumpet John Hagstrom, who performed in later sessions under the conductor.

London’s production team used the latest in splicing and mixing techniques to help Solti achieve his sonic ideal, which in turn became a benchmark for live performances. “He knew how he was going to sculpt the best takes to create the best recording that he could get,” Hagstrom said. The orchestra would repeatedly drill a passage “until the playing was super-together. Then you’ve got it.”

Among the era’s celebrated LPs was a 1972 account of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, recorded at the Krannert Center in Champaign-Urbana. Jacobs later recalled how Solti sought a fuller tuba sound in the work’s Dies Irae, so he had a microphone placed in front of himself and second tuba Roger Rocco. As the story goes, the tubas repeated the passage with the new microphone placement, only to quickly drown out the bassoons. “Maestro, we can’t hear the bassoons,” an engineer cried out from offstage, to which Solti answered, “I don’t care about hearing the bassoons!”

“I can honestly say that I was never even aware that the bassoons were playing along with us because we were so loud,” Jacobs concluded.

Mahler as ‘Theme Song’

Mahler’s extravagant Fifth Symphony became a particular calling card on CSO tours and admirers flocked to hear Herseth deliver the opening solo with a customary martial focus, his face sometimes glowing red as a radish (“It shows I’m trying,” Herseth would joke). “Our theme song with Solti is Mahler’s Fifth,” Clevenger told The Instrumentalist magazine in 1990. “Some of our best concerts we ever played were with that piece.”

Solti agreed, noting in his Memoirs that “it was Mahler’s Fifth which I shall always associate with the Chicago Symphony.”

But it wasn’t all Romantic masterworks in which the brass shined. Herseth and Clevenger made crisp recordings of concertos by Mozart and Haydn, respectively, with Assistant Conductor Claudio Abbado. Jacobs had a rare solo turn in Vaughan Williams’s Tuba Concerto under the direction of Daniel Barenboim. And long before Barenboim succeeded Solti as Music Director in 1991, he recorded the complete Bruckner symphony cycle in the brass-friendly Medinah Temple (symphony cycles were often remade in later years as digital recording technology became available).

The brass sound acquired a new focus in the mid-1980s, when the horn section took up instruments by Chicago craftsman Steven Lewis. Second Horn James Smelser believes the Lewis horns allowed for greater flexibility in a wide repertoire. “Besides being just uniformly in tune, they are just very malleable to different tone colors,” he says. “That’s a huge thing in our horn section.”

Meanwhile, the era saw a changing of the guard. The revered Bass Trombone Edward Kleinhammer retired in 1985 after a nearly 45-year tenure. He was succeeded by Charles Vernon. Jacobs retired three years later, to be followed in the Principal Tuba chair by Gene Pokorny. And Frank Crisafulli, a CSO member since 1938, retired from the Second Trombone position in 1989, to be succeeded by Michael Mulcahy. All three successors remain with the orchestra.

Some longtime observers contend that Solti had steadily dialed in the brass section’s more muscular tendencies, particularly during the 1980s. “Over the years there was a very, very long diminuendo,” says Friedman, recalling how, in later recording sessions, engineers even questioned whether the brass were too soft. But the section also acquired a refinement and sense of blend with other parts of the orchestra.

“The Los Angeles Philharmonic [brass players] used to call us ‘the wall’ — and they didn’t mean it as a compliment,” Friedman continues. “I can understand why they thought we were a little bit animalistic. The difference now is we’ve lost some raw excitement but hopefully replaced it with a lot more subtlety and blend.”

Next: The series concludes in the Riccardo Muti era.

Disclaimer: I am the producer of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s radio broadcasts and write other copy for the orchestra. This article is unaffiliated.

Leave a Reply