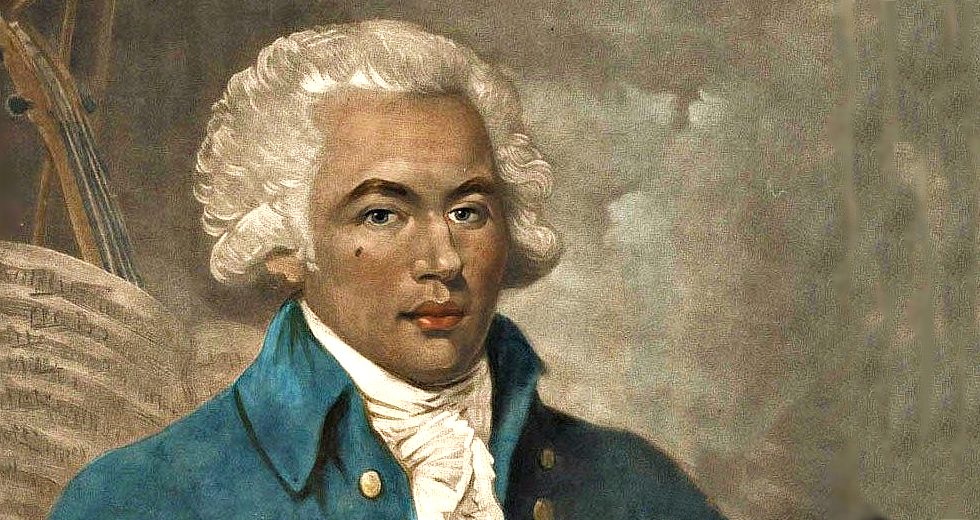

As concert presenters overhaul their programming amidst the pandemic, several are taking up the works of Joseph Bologne, better known as the Chevalier de Saint-Georges. Bologne’s largely unsung chamber music, symphonic and even operatic repertoire is turning up in advance of a planned Hollywood biopic, and mirrors a larger racial reckoning across the United States.

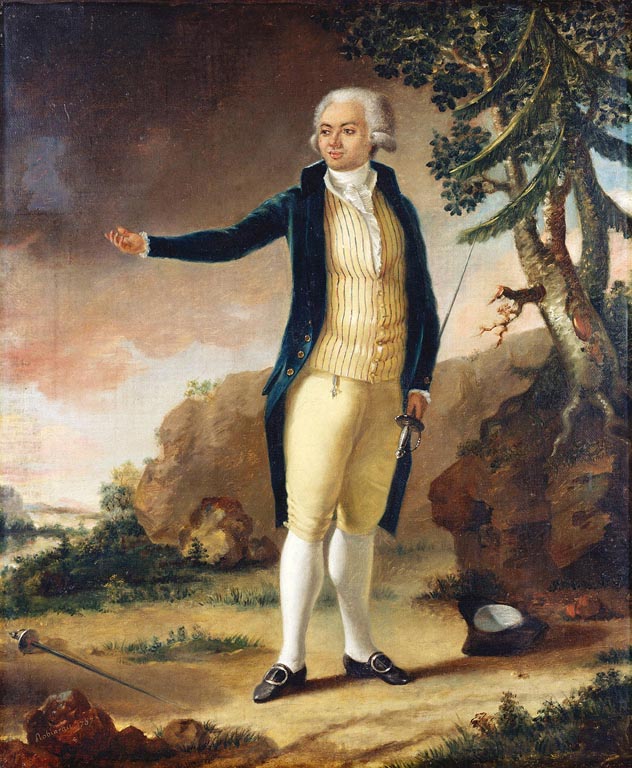

Regarded by scholars as the first Black composer of importance, Bologne led a life worthy of an adventure novel: he commanded an all-Black regiment during the French Revolution, spent 18 months in prison, led one of France’s top orchestras, composed in nearly every major genre of the day, and excelled as a virtuoso violinist and a champion fencer.

In researching Bologne’s life and career for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s website, I found that his notoriety as a swordsman has, among historians, drawn as much interest as his musical accomplishments.

Champion Fencer

In By the Sword: A History of Gladiators, Musketeers, Samurai, Swashbucklers, and Olympic Champions (2003), author Richard Cohen devotes several pages to Bologne, who he describes as “a quick learner [who] excelled at a range of accomplishments.” Cohen adds, “By fifteen he was already a formidable foilist; by sixteen his speed and sense of timing were famous… Saint-Georges was also one of the best shots of his time; one of his feats was to throw up two crown pieces in the air and hit them both before they struck the ground.”

In The Encyclopedia of the Sword (1995), author Nick Evangelista writes that “besides fighting many duels, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges was the co-originator, along with the French fencing master La Boëssière, of the fencing mask.” Evangelista goes on to relate how Bologne didn’t take unfair advantage of his skills. Once, he was confronted by an officer of hussars [a light cavalry], “who, not realizing who he was, boasted of having crossed swords with, and beaten the famous Saint-Georges many times.” Evangelista continues:

“Saint-Georges, knowing this to be false, calmly asked the young man to fence with him, which the unfortunate soldier readily agreed to do, thinking he would impress the ladies who were present. Saint-Georges then proceeded to make one hit after another, virtually at will. He ended the exhibition with a dramatic disarm. At this point, Saint-Georges revealed to his shamed opponent who he actually was. The young officer left the house immediately and never returned.”

Bologne was born in 1745 to Nanon, an enslaved woman from Senegal, and George Bologne, a wealthy sugar plantation owner in Guadaloupe, in the West Indies. George took him to France at age 8, and five years later, enrolled him in an elite fencing academy where he studied with the aforementioned La Boëssière. As a teenager, Bologne’s fencing prowess brought him fame throughout Europe as he participated in dueling contests in Paris and London. In one match, he beat Alexandre Picard, a fencing-master of Rouen, who had taunted him with racial epithets. For his victory, Bologne’s father rewarded him with a horse and buggy.

While fencing opened doors for the Chevalier — as did his violin virtuosity — he was subjected to racist abuse. Despite traveling in aristocratic circles, he could never marry into that milieu because of his skin color. When, in 1976, the Paris Opéra considered him for the post of music director, a group of leading singers successfully petitioned Queen Marie Antoinette to spare them from “having them submit to the orders of a mulatto.”

As a composer, Bologne distinguished himself in the major instrumental forms of the day, writing a series of sonatas for one and two violins. Below is an excerpt of the Violin Sonata in A Major, No. 3, featuring brothers Matous and Simon Michal, both members of the CSO violin section (the full performance is available on the streaming platform CSOtv).

Leave a Reply